John Ward &

Dr Maria Nilsson Recent research and discoveries at Gebel el-Silsila

11th January 2021

Dr Maria Nilsson & John Ward

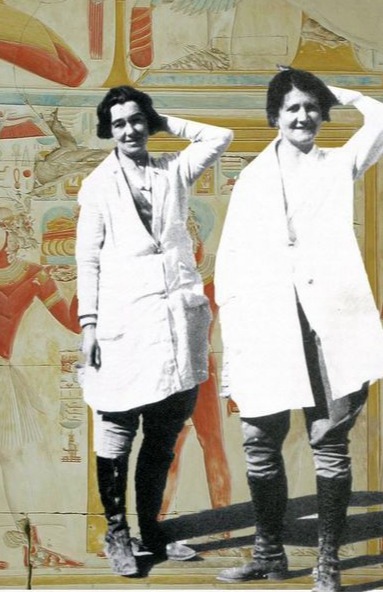

John and Maria joined us via Zoom. Maria was quite familiar with this , but it was John’s first experience. They have been excavating at Gebel el-Silsila since 2012 and introduced us firstly to their hard-working team, with whom they have made a number of remarkable discoveries over the last eight years. Due to Covid-19 restrictions physical presence at the site for the 2020 season was not possible, but instead they took the opportunity to undertake a thorough review of material from earlier years and have published a number of papers.

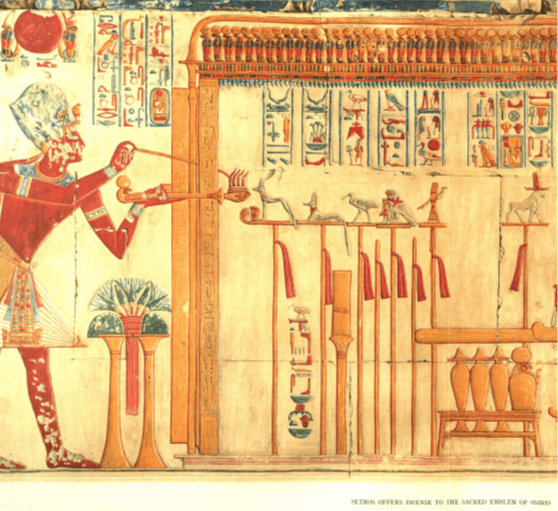

The site covers an area, on both the West and East banks of the Nile, of 30 square kilometres and, although the majority of their work has concentrated on the New Kingdom, it is clear that, from an Ancient Egyptian perspective, the area was occupied from about 8500 years ago right through to Roman times. Previous scholars have focussed primarily on the quarrying aspect, this being the primary source of Nubian Sandstone used in monumental building projects throughout Ancient Egypt. Maria and John, however, have taken a much broader approach taking into consideration ancient rock art, inscriptions form all periods, settlement activity and infrastructure as well as the 104 quarry sites.

Some of the main areas they have worked on include a worker’s village on the West bank situated on the plateau above the quarry of Tutankhamun. 41 structures have been uncovered in a small town, together with roads, quays and other infrastructure. It seems likely that this was a re-use of an earlier site and, later, the archaeology shows that the area was again used in Roman times.

Moving to the East bank, excavations started in 2015 at the Temple of Sobek. This site was very poorly preserved and had been dismantled in antiquity. Evidence was found from the time of Rameses II and there were also earlier finds from the 18th Dynasty. Interestingly some remains of limestone were found there. It was during the reign of Hatshepsut that the significant shift from building with limestone to sandstone took place. Very close to the Temple another structure was uncovered, which has been called Sobek’s Den. Excavation through many layers has brought to light crocodile remains and further clearance is planned when the team can restart work there.

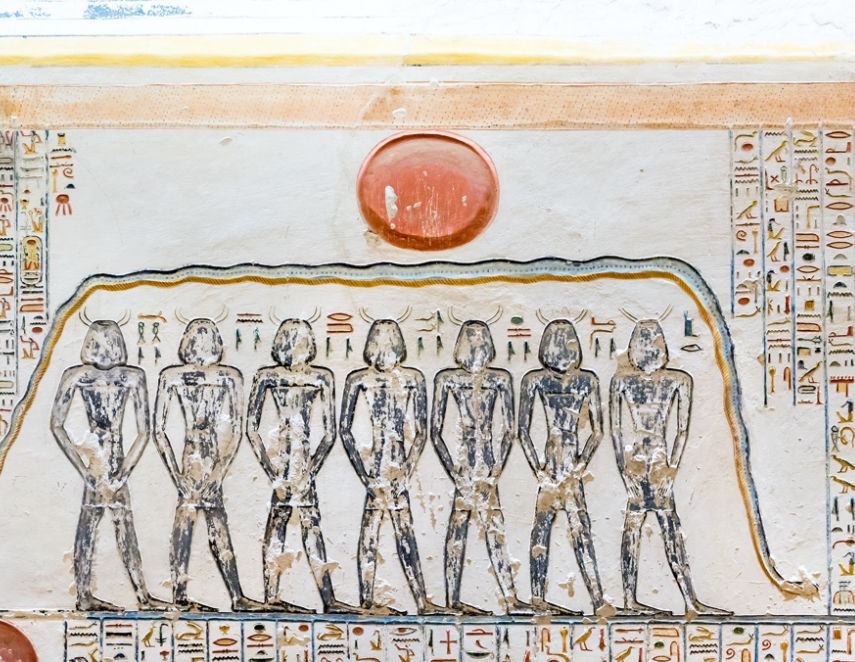

A little south of the Temple and still on the East bank, a necropolis was discovered but it is in a poor state, due to corrosion by Nile silt from countless inundations reaching the area over the years and current water table issues. So far 73 tombs have been documented; 33 rock cut chambers and 40 crypt burials, including 2 shaft tombs. There are no inscriptions inside any of the tombs, but there are an intriguing number of images of feet. It would appear that the necropolis was used for around 200 years. The primary use seems to have been in the Thutmosid period, though activity ceased before the reigns of Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV, and there appears to have been some further use in the 19th and finally the 20th Dynasties. From the style of the burials and the funerary objects recovered, it is apparent that this necropolis was not used for the poorest people in the community.

Exciting work has also taken place in an area relating to the time of Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV and John and Maria will shortly be publishing a paper on this. They very much hope to return to Gebel el-Silsila in 2021 to renew excavations on this area in particular and other parts of the site.