January 2024

Dr. Backhouse began by showing a picture of a sycamore growing in Egypt today;(Ficus sycomorus) this is not the same variety we see in the UK but one with edible fruits providing nourishment, timber and shade. She went on to consider how the majority of the gods and goddesses in Ancient Egypt were often portrayed in multiple forms, human, animal and as objects and likened them to a vase. We can think of the gods as the empty vessel that could be filled with any of the 3 identities.

Trees, being one such identity, were used by many of them with Hathor, Isis and Nut as prime examples. A good illustration of this is found in the tomb of Sennedjem. He and his wife are shown in the Field of Reeds with lush farmlands and an orchard, mirroring a scenario from the afterlife which they hoped to achieve. The trees represented in part of the scene appear to be Ficus Sycomorus which are cultivated all over Egypt, though are probably originally native to Southern Africa. In the tomb of Meketre, 24 small models were found depicting an idyllic life. These included butchers, brewers, weavers and a model of a garden with a pond area that could be filled with water. The trees in this garden would provide a delightful shady area for leisure.

Many goddesses can represent water or breath. Today we understand that as trees add oxygen and remove carbon dioxide from the air they have a practical use in improving air quality. Perhaps the Ancient Egyptians grasped this subconsciously, without having a scientific understanding of the process of photosynthesis. The wood obtained from the native trees, though often of poor quality, was valued, amongst other things, for the construction of coffins, such as the 6th Dynasty coffin of a priestess of Hathor displayed in the British Museum (EA46634 BM). Coffin texts often show the deceased greeting a goddess in her tree form. Many tomb paintings show scenes of sycamore fruits and wood being harvested.

Pairs of sycamores have an important association as part of the essential cycle of day to night to day, based on the travels of the gods and the deceased through the underworld and back into the light. The pairs of trees were associated with general offerings at first but later with individual goddesses, especially with those whose title was ‘Mistress of the Sycamore’. This title was also linked with the goddess Hathor, a major national goddess who was often called ‘Mistress of the Sycamore in all her places ‘. A statue of Menkaure in the Cairo Museum shows her empowering him to carry out his jubilee Hebsed ceremony.

Many early priestesses were the daughters of the king but later we start to see non-royals taking on this title. The worship of Hathor as Mistress of the Sycamore probably started at Memphis, although it is not possible to know this for certain.

One of the coffin texts from the First Intermediate Period says :

Where it is granted for you to eat

Say they who are there

Under the branches of the sycamore

I desire it

Together with the musicians of Hathor.

This shows an idealised picture of the afterlife with a depiction of two trees with the sun rising between them. In KV34 Tuthmosis III is shown suckling and taking sustenance from a tree, combining the concepts of the goddess Isis as a tree and his mother; a cleverly devised reference to fertility and nurture. In the tomb of Sobekhotep there are two representations of him and his wife or a goddess, who emerges from a tree and presents fruits, giving him permission to eat. They are by a lake full of solar symbols such as water lilies and tilapia fish which are representations of rebirth and suggest he is reborn in the afterlife. In the tomb of Nakht (TT52) from the reign of Amenhotep III, goddesses are shown wearing trees on their heads as symbols. The false door shows relatives bringing offerings. Two sycamore trees are shown on his Book of the Dead, placed in the coffin to help him transfer successfully to the afterlife and then be reborn like the sun. In the tomb of Khabekhnet the deceased, attended by Anubis, is accompanied by the goddesses Isis and Nephthys with a tree on either side to create a space for the transformation to take place.

At Dendera, the goddess Nut is shown using two ished trees to direct the life-giving rays of sun to the temple dedicated to a local form of Hathor. Nut is named in the tomb of Khensumose, priest of Amun-Ra (21st Dynasty), who stands in front of a tree giving sustenance to him. Some papyri are also a source of illustrations of the veneration of tree goddesses, showing the deceased sitting under a tree in the afterlife or often the tree stands in a pot on a small table and is adored. In the tomb of Qenamun, chief Steward of Amenhotep II, a tree is named as Onn, a representative of the goddess Nut. Similarly in the tomb of Sennefer (TT96) he is shown venerating an ished tree as a manifestation of Isis. This symbolism becomes incorporated into the Garden of the West; the ideal garden to which the family could withdraw. The tree is linked to water and shows the whole agricultural cycle of the year. No two trees are painted the same, showing the infinite variety in the garden.

Nut, Hathor and Isis are often shown in human form with a symbol on their head, or we sometimes see a local manifestation of these goddesses, such as Imenet as a local variant of Hathor. Another example in Nakhtamun’s tomb has Taweret as a representative of Nut as a tree. The scene continues to show a djed pillar with Isis and Nephthys and a composite god, representing rebirth. Later in the 18th Dynasty trees are often shown personified with hands reaching out from inside. A representation of Ramesses II from Deir el Medina, shows him being breast fed by Nut under a sycamore and this is the focus of the whole scene.

Dr. Backhouse, through her richly illustrated lecture, linked earthly life and the afterlife with tree goddesses. Trees provided food, shade and wood in both this life and the next and assisted in the passage of the deceased between the two. She also highlighted the association with water and breath, necessities in both earthly life and the afterlife, and demonstrated comprehensively how and why tree goddesses were so venerated in Ancient Egypt.

February 2024

The Society was pleased to welcome back Megan to give us another very interesting lecture on the subject of her PhD research – paddle dolls.

On first glance, they look rather like wooden spoons or miniature wooden paddles. She was first inspired to undertake this research after seeing the examples held in the Atkinson in Southport. There are only a relatively small number of these objects which, almost exclusively, came from the 11th and 12th Dynasties and, in Museums around the world, there are only 30 collections holding examples. The Atkinson is, therefore, very fortunate to have three. Prior to Megan undertaking her research they had not previously been studied in very great detail and there is so much more to reveal about them.

Megan showed us a number of examples in these 30 collections, including three from the Met and others from Boston, Leiden, Manchester, Swansea, Liverpool, Scotland, Cambridge, Stockholm and, of course, Southport. Whilst all have many similarities and are instantly recognisable as paddle dolls, the side by side images illustrated very clearly the differences between the dolls in terms of size, shape and decoration. The different elements of decoration include clothing in checkered, herringbone or diamond design, necklaces, dotted cross-over lines, tattoos and figure motifs, generally of Bes or Tawaret, and elaborate hairstyles. Some are fairly plain and representative, some highly decorated with a more shaped torso, often painted or inked with pigment. They all tend to be similar in shape with a bulbous lower end and usually a rounded base. The arms are truncated and there is a strong focus on the pubic region.

Locally, some can be found in the Atkinson Museum in Southport, and in both the Liverpool and Manchester collections. The Atkinson examples show differences in construction and preservation. One shows evidence of considerable damage. The length of the arms and legs suggest it is truncated and the base is squared off, with most of it missing. Most of the hairpiece is also lost. Another is covered with a white residue and again damaged at the base with little hair. The third has a hairpiece that seems to have been bulked out with straw, possibly added later to make it more saleable as, on close inspection, it looks like two pieces joined together. The grain of the wood can be clearly seen on the paddle doll in Liverpool’s World Museum and there is very little decoration. It is shorter and wider at the base than most examples and the very full hairpiece is quite different, being made of coiled linen strands on a linen base, rather than mud beads. The Manchester doll is more like the Atkinson dolls and is quite plain in design with some pigment decoration.

The Egyptologist Herbert Winlock, described paddle dolls as “barbarous looking things whittled out of thin paddles of wood, gaudily painted and with great mops of hair made of strings of little beads of black mud ending in elongated globs.“ This rather dismissive attitude prevailed for some considerable time, before any more serious academic study began.

Some museums now arrange activities involving children making paddle dolls as part of their educational programme because they can use bright colours and string for striking hairstyles. The work of a local artist, Emily Burke, has been influenced by them and Pagan Portals make similar objects but puts an emphasis on magical aspects and witchcraft.

But what was their function? Were they simply playthings placed in tombs as children’s toys as Garstang suggested? Herbert Winlock considered them as possible concubines for the afterlife where they were found placed in men’s tombs. Ellen Morris has made a more in depth study of one body of paddle dolls found near Deir el Bahri considering a number aspects, relating to the dolls themselves and associated tomb deposits, including location, tattoos, demographics, mirrors, costumes, music, general exposure and menat necklaces. She believes that this group could have represented dancers and musicians of the Khener Dancers connected to the court of Hathor. These are also seen in tomb paintings and texts particularly in the area around Deir el Bahri. The collection she studied had dolls in varying sizes and she felt this was a reflection of the make-up of the actual troupes which incorporated children, young girls and adult women. She also questioned whether the different costumes and tattoos distinguish between different types of dancers or singers. She considered whether there was an association with the goddess Hathor, who exposed her pubic area to her father, the god Ra. A further apparent connection to the goddess might also be seen in the associated menat necklaces and mirrors in the burials, both Hathoric emblems, or do some of the dolls represent Hathor herself as some show signs of a covering of gold leaf or paint?

When she started to look at paddle dolls, Megan said she did not think they always had hair. After researching in more detail, however, she now believes they all started out with hairpieces. The example in the Victoria and Albert Museum, missing its hair, has a resin residue still attached to the head. Other examples have a few strands attached to a coiled piece of linen with a little hair remaining and yet others appear to have mud stuck on the front. This is easier to identify on the examples made of wood or bone. The British Museum has some very rare examples of linen dolls that have very similar hair attachments. There are some regional differences to be identified in the hair attachments. It seems all were added on completion, with ‘hair’ often sewn onto a skull cap shaped piece of linen which was then glued onto the doll with resin. The hair could be mud beads or coiled or knotted linen.

Unfortunately many examples come with little or no provenance. Some fakes were bought by Joseph Sands and show the same motifs, style and colour as known originals.

Their true purpose is still not clear. More research is still needed that will look at all the dolls in the museums spread across the world and ideally include those in private collections, try and link them with other material culture of the time, establish if there are regional differences, look for links between the tombs they were found in and look to separate fact from myth in respect of what we really know about these archaeological oddities.

photo - Cheryl Tempest taken at World Museum, Liverpool

March 2024

Creatures of the Nile.

Gina is putting on an exhibition this year at Liverpool’s Victoria Gallery and Museum entitled Creatures of the Nile, to run from 4th May to 5th October 2024, and she treated the Society to a detailed preview through her lecture.

The exhibition includes animals from the Nile Valley and Sudan, which call the Nile home and considers the natural environment as a whole, drawing on material culture primarily from the Garstang’s own collection as well as loans from other museums, principally Manchester and the World Museum. Many of the object are not just art, they also have a function. The fact that the Nile runs though many different areas and environments is highlighted, with the joining of the Blue and White Niles at Khartoum and flowing all the way to the delta emptying out into the Mediterranean. The exhibition demonstrates how this long expanse of river was inhabited by Egyptians and Nubians from neolithic times right through to the Roman and Byzantine periods.

The fertility of the Nile aided a flourishing of human settlement from very early times and these people left behind images of animals that impacted on their lives. The habitat consisted of the river at its centre, green fertile strips on either side, leading off to the desert east and west and above it all the sky, with its bounty of birds; some seasonal and some permanent. The desert was not always the hostile, arid environment we see today and until about 5000 years ago was more savannah-like in parts. Finally, in all areas, there were the insects.

The river was teeming with life. Many tomb scenes represent this vast variety, although it is not always easy to identify specific species in the paintings. Some fish, however are very easy to spot, such as the tilapia and catfish. The banks often have dense foliage packed with ducks and geese. But not everything is benevolent and crocodiles and hippos often feature in fishing and fowling scenes. Many examples of these ferocious creatures are found in the material culture from the predynastic times onwards.

The land, incorporating the margins by the river, the grasslands/savannah and desert edges, is again often seen on tomb walls; Khnumhotep at Beni Hassan is depicted on a desert hunt chasing wild animals. But domesticated cattle and donkeys are also represented in art, both in painted images and, in the Middle Kingdom, in the form of models taken into the tomb for the afterlife. These domesticated animals were important both as a food source and beasts of burden. There was competition for the resources of water and fodder between the two groups and the wild animals could present significant danger with leopards and lions present. Leopards often formed part of priestly attire and lion representations featured through time in both Egypt and Sudan. Hyenas are not seen very often in material culture, so the Garstang is very fortunate to have three examples.

In the sky falcons were the most commonly known and depicted birds with many deities connected to them, starting with the hawk deity at predynastic Hierakonpolis. Another prominent bird in the iconography is the ibis, associated with Thoth, and vast numbers of mummified ibises used as votive offerings have been uncovered. Again in the imagery some of the birds are easily identifiable, but this is not always the case, especially in some of the earliest examples.

Insects are often overlooked, but form an essential part of the ecosystem. It appears that they are not often included in imagery, but closer inspection can reveal dragonflies, grasshoppers and bees, which of course were very important with their royal connection.

There was a very close connection between animals and the divine, with gods often shown as an animal or with animal attributes, being a manifestation of the power of that particular animal. The Lion manifests as Apademak in Sudan and Sekhmet in Egypt. Harnessing the danger and making it work for, not against, them is a key element well illustrated in the various snake-related deities. Hippos as powerful and aggressive creatures are perhaps not an obvious choice for a sympathetic and caring goddess like Tawaret, but they are at their most aggressive when protecting their young, so perhaps are emphasising maternal instincts. However, not all of the animals chosen were ferocious, such as Hathor being represented as a cow.

An example of an actual sacred animal is the Apis bull and the burials at the Serapeum attest to its importance. Otherwise animals were used in huge numbers as offerings to the associated god; cats for Bubastis, ibises for Thoth, dogs for Wepwawet. Mythical creatures also feature in both Egypt and Sudan such as the Ba bird and most famously the sphinx.

The use of animals by humans varied. They were a food source but also used in agriculture and for transport. When used as food, the non-edible parts did not go to waste and bones, hides, shells and feathers were used as raw materials for tools and decorative objects. Raw materials were also obtained from wild animals captured in the river and in desert hunts. Leopard pelts, ostrich feathers and ivory were highly prized and often feature on furniture, jewellery and clothing, with the imagery used as the decoration, rather than the animal itself. In writing a very large number of hieroglyphs are inspired by the natural world.

Over time different animals appear and disappear in the artistic repertoire indicating changes to the environment – some natural and some caused by humans. Elephants, giraffes and lions disappear from Egypt mostly from climate change but later introductions are also made with horses, chickens and camels. Human settlement impacts on the wild life by pushing it to the margins and hunting, frequently with dogs, and there are many representations of the tools and weapons used to catch fish, animals and birds from the river, land and sky.

Exhibition runs until 5th Oct 2024. https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/garstang-museum/news/articles/university-gallery-explores-world-of-ancient-egyptian-and-sudanese-animals/

April 2024

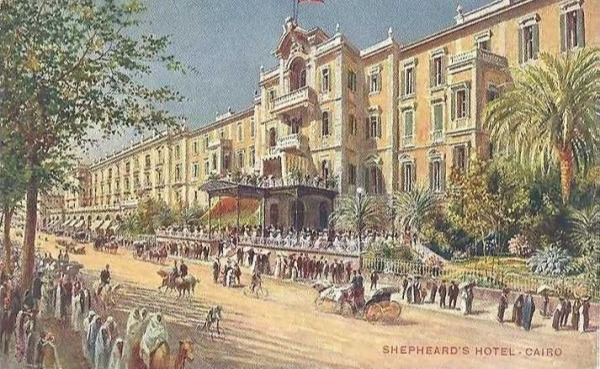

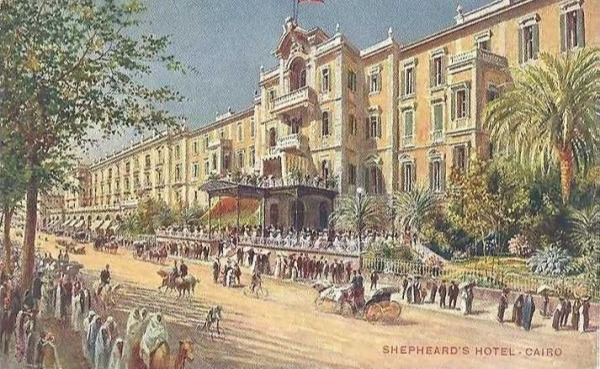

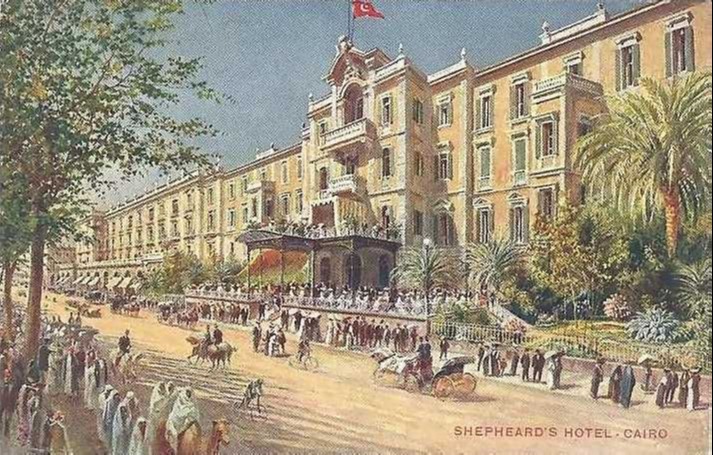

Egypt has had its fair share of Grand Hotels and universally accepted as the grandest of all was Shepheard’s. Of course in the early days of these luxury hotels, staying there depended very much on one’s status in society.

Lee took us back in time to look at how and why hotels first began. Accommodation offering facilities to guests was known from early Biblical times. The Romans offered lodgings – an example was found at Pompeii – and they were the first to introduce thermal baths. Later caravansaries popped up along the Middle Eastern trade routes and in the UK Abbeys took in travellers before inns were developed and staging posts, where horses could be changed. Hotels also developed to cater for pilgrims and crusaders to the Holy Lands. France was the first country to introduce a law requiring a register of guests to be kept and the UK soon followed suit. The very first guide books for travellers were also published in France. The building of hotels really blossomed in the 19th century after the industrial revolution.

Before tourism took root, in the early days of travel to Egypt, the majority of people were just passing through and arrival at the port of Alexandria was the way to facilitate this. A few arrived in Egypt as invalids looking for a better climate, but most were en route to India or other parts of Africa. They generally spent only one night there before moving on and the standard of accommodation was not particularly exciting. However, in 1887 the luxurious San Stefano hotel opened its doors. It faced the sea, had a full length latticed veranda and many facilities and gardens and soon became very popular, especially with the Cairo elite escaping the heat of the capital for the Summer months. Initially it only opened over the Summer, but later as guest numbers grew it remained open all year. More hotels were built, including the Cecil, but the San Stefano remained the most fashionable. However, after 1900 revolution and the departure of the more prominent families led to a decline and it wasn’t until Alexandria was seen as a place for tourists to visit in its own right in the 1980s that it finally began to revive. But in 1993 the San Stefano closed its doors and was subsequently demolished. The Four Seasons now stands on the same site.

In the early 1800s there were a few, but not many hotels in Cairo; Hill’s was the oldest, with D’Orient, Levicks and the Giardino as its competition. In 1850 Samuel Shepheard opened Shepheard’s and by the end of the century this was one of the most famous hotels in the world. Cairo was transforming at the same time as Shepheard built his hotel with a new city being created at the side of the old one and more hotels were built, such as the Grand Continental, to coincide with the opening of the Suez Canal. But there were also quite a number of new more humble hotels to cater for the ever growing numbers of tourists. At one point the numbers spiralled to such an extent that steamers on the Nile were drafted in as floating accommodation. Shepheard’s remained the choice of the elite and the terrace there was a famous and popular meeting place. In 1890 the hotel was torn down and replaced by a lavish structure with Italianate architecture. The interior was very grandiose and the hotel boasted 340 bedrooms and 240 bathrooms. The number of bathrooms was remarked on as very generous! Competition between hotels was fierce and they all strove to up their game with many alterations and additions. But through all this Shepheard’s stayed at the top. Post war many viewed the hotel as a seat of imperialism and disaster struck in 1952 with an arson attack by rioters. The hotel was totally ruined and never rebuilt. The plot on which it stood remained empty until the last years of the 20th Century. The hotel we currently know a Shepheards is in a different location and thoroughly modern.

The pyramids were visible from the city but there was no road there and the Nile had to be crossed by ferry. An expedition to the pyramids took two days by donkey. There was only basic accommodation there, which wasn’t to the liking of wealthy visitors. But then an English couple who had acquired the famous hunting lodge overlooking the pyramids, built a hotel at the side of their home and in 1886 the splendid Mena House opened. For their guests they ran a coach and four from the hotel to the Thomas Cook office in Cairo, until a tramway was completed, at about the same time as electric lighting was introduced. Tea on the terrace was very popular. Since those days there have been numerous additions and changes of ownership, with the result that the hotel looks very different to us today.

Moving south to Luxor, the Winter Palace is of course the grand hotel there. It opened in 1907 and, although there were quite a number of existing hotels, these were much more modest. The Winter Palace was built on a much larger and grander scale – an orchestra played in the vestibule - and it was always intended as the pre-eminent hotel. Within a week of opening it was full, attracting superior guests and, of course archaeologists. Lord Carnarvon made it his base of operations. In the 1960s and 70s air travel enabled a huge increase in tourism and many more hotels popped up in Luxor, but the Winter Palace always retained its place as the grandest and, despite many refurbishments and restorations over the years it still retains its character today.

Heading further south again, to Aswan, Lee’s chosen grand hotel was of course the Old Cataract. In the 19th century it took two days sailing to reach Aswan, until the railway opened in 1898. This was at about the same time that construction of the first dam began and word of how beautiful the area was soon spread, bringing an influx of tourists. Thomas Cook steamers brought many passengers, who initially had to stay in the few existing small hotels. Another steamer company set itself up as rivals to Thomas Cook and they built their own hotels to cater for their guests. Thomas Cook’s response to this was to outdo them with the construction of the hugely imposing Old Cataract, opening in 1899. It initially had 120 rooms, nearly all looking over the Nile and quickly proved so extremely popular that tents had to be erected in the grounds to accommodate the overflow of guests. In 1902 a third storey was added, bringing the room total to 220 and the hotel still looks the same today. The large veranda overlooking the river was immediately one of its most popular features and remains so to this day.

The Old Cataract also had its fair share of famous visitors including Agatha Christie. Whilst it is known for certain that she stayed there, it would be lovely to think that she penned Death on the Nile whilst at the hotel, but sadly there’s no evidence to suggest that she actually did.

May 2024

Over the years many different aspects of Senenmut have been debated academically. In his lecture Campbell concentrated mostly on his possible influence on Hatshepsut’s building programme and asked the question, was Senenmut the real mastermind behind its success and the innovations?

Hatshepsut regarded the god Amun as the most important figure in her life and claimed to be his daughter. Her role, before taking the throne, was as the God’s wife and she proclaimed that the buildings she created were to enhance his glory. Undoubtedly if she had been male she would have been one of history’s greatest rulers; but how much was due to her own ability and how much to Senenmut’s support?

Senenmut’s background is unknown, other than that he originally came from Armant. It is however certain that he was not from the royal family or the royal household, so it was very unusual for him to rise so high in the ranks. But we are in no doubt of the high position he achieved as, in the typical immodest way of the Egyptian elite, he tells us so himself! He listed his multitude of titles, which included that of Overseer of all Royal Building Works.

He claims he is “ ignorant of nothing that has happened since the beginning of time” and states that he is an innovator who “creates images never used before”. The latter is evident in the various statues he commissioned. We know of 26 statues of Senenmut, a completely exceptional number for a non-royal, and many have very new and different elements, which must have caused quite a sensation at the time. He produced block statues (a well-known one found at Karnak now resides in the BM) of him sitting with Neferure, Hatshepsut’s daughter, on his lap with her head under his chin. This must have seemed like shockingly intimate contact with a royal personage. Another innovative style was a statue of him kneeling with an obelisk as the back support (in Cairo Museum). Inscriptions from early in Hatshepsut’s time, and before she showed herself decked out in pharaonic regalia, show Senenmut taking instructions from her for the production of massive obelisks to be erected at Karnak to the glory of Amun – another major innovation.

Decoration at Deir el-Bahri also shows previously unknown traits. At the top of the wall in the Anubis Chapel a serpent, a ka and a sun disk spell out Maatkare; the same rebus is used at the front of the kneeling statue. Images of Senenmut himself in a kneeling position are found in a number of places in the temple behind the wooden doors, which kept certain areas out of sight. This has never been seen before, but an inscription by Senenmut tells us that this has been done strictly with Hatshepsut’s permission. Whilst looking through the storerooms at Manchester Museum, Campbell found a statue fragment, which again appears to show Neferure sitting on his lap wrapped in a cloak. This piece was found near Deir el-Bahri and would mean that he had statues placed at either end of the processional route of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, which is again exceptionally unusual for a non-royal and would stress his closeness to Hatshepsut.

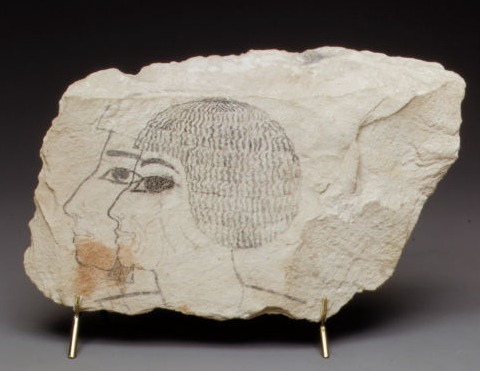

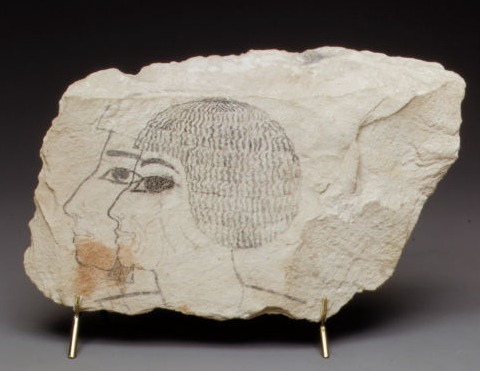

For his afterlife Senenmut had two tombs prepared, both very close to Djeser Djeseru. The higher one was never intended to take his burial, but the lower one had a very, very long corridor leading down underneath the temple. In the upper tomb an ostracon was discovered showing two images of Senenmut’s face, possibly a template for use in the decoration programme. However on the reverse was a picture of a rat. Was this a comment on how Senenmut was viewed during his lifetime?

After Hatshepsut died much of her imagery was defaced and this also happened to some of Senenmut’s images, but not within the precinct of Karnak. Statues of him found in the Karnak Cachette showed no deliberate defacement; indeed one has signs of repairs in antiquity. One shows water damage consistent with being washed by the annual inundation over very many years, suggesting his fame and high esteem lived on, even if the rat image might imply that this was not quite how he was viewed by everyone in his lifetime.

We are all looking forward to Campbell’s book on this subject, due to be published next year.

June 2024

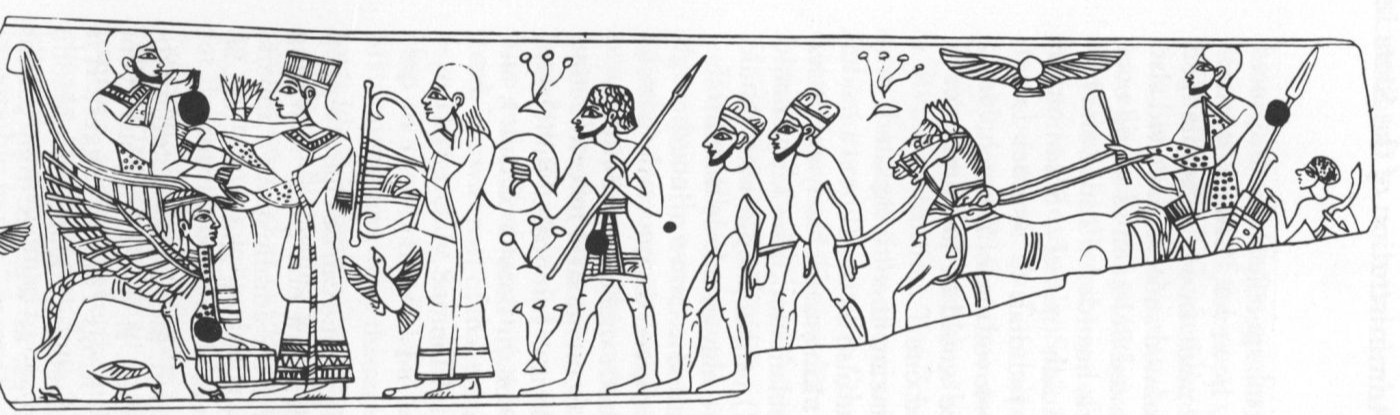

Gina began her lecture by examining a scene from the tomb of Menna, a typical Nilotic representation of the river and surrounding plants. What did this imagery mean to the early Aegeans and why did some Mycenaean artefacts show designs with Egyptian or Egyptianizing elements, such as the 16th Century BC bronze dagger in the Archaeological Museum in Athens with a riverbank scene engraved along the central panel?

She clarified the terminology she would be using with Minoan referring to Crete, Cyclades the Greek Islands and Mycenaean mainland Greece. She also provided dates for the chronology with the Early Bronze Age spanning 2000- 1900 BC, Middle Bronze Age1900-1600 BC and Late Bronze Age 1600-1050 BC.

Gina questioned how the Aegeans as a whole learned about Egyptian iconography. They certainly moved around the Eastern Mediterranean as traders, probably sailing anti clockwise. A shipwreck was excavated from 1984 to 1994 off Uluburun on the Turkish coast and was found to have a large cargo of prestigious objects, some of which were Egyptian, including a scarab naming Akhenaten’s wife Nefertiti in gold showing signs of wear.

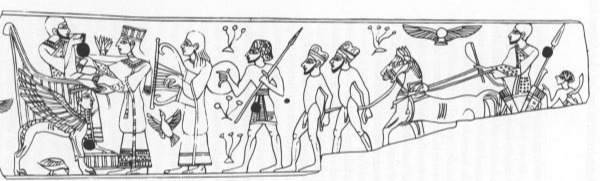

Aegean people featured in some Egyptian tombs, with a number of tombs belonging to 18th Dynasty nobles from the reigns of Hatshepsut, Thutmosis III and Amenhotep III showing people referred to as ‘men of Keftiu‘, the Egyptian name for Crete, and more are depicted on a statue base at Kom el Hettan.

Evidence was also found during excavations at Tell el Dab’a, where New Kingdom palaces were discovered decorated with non-Egyptian motifs. They were no longer in situ, having apparently been removed from the walls, but fragments clearly showed scenes included bull leaping, griffins and lions; all painted with Aegean methods and imagery that was not Egyptian. The bull leaping fresco is remarkably similar to those found in Knossos and the griffin shows non Egyptian features. The lion hunting scenes on the frescos show very close similarities to one found on another Aegean dagger.

Curiously this evidence does not seem to help with the interpretation of Nilotic scenes in Aegean lands as they are generally dated earlier than their Egyptian counterparts, with some as early as the 19th and 18th Centuries BC. They pre-date the Tell el Dab’a palaces, the volcanic eruption on Thera and Mycenaean shaft graves, as the images in the Theban tombs mentioned above date to the 14th Century BC. This begs the question - what were the really early Nilotic scenes? Numerous examples are to be found; Quartier Mu, Crete, a terracotta Sphinx (1750-1700 BC) with long flowing Aegean locks and a rock crystal bowl (1600 BC) with Minoan grave goods. In December 2019, a new discovery was made at Pylos. Family tombs were found dating from the 15th Century BC containing quantities of flakes of gold from the wall or floor along with a pendant of Hathor, clearly Egyptian in manufacture but found in this Aegean area.

Gina then looked at a case study by Andreas Vlachopoulos and Lefteris Zorzos of the West House at Akrotiri, on Thera (now Santorini). The volcanic eruption in the mid 2nd millennium BC created a catastrophic tragedy but, as at Pompeii, it resulted in great preservation of the site giving a windowon to life at that time. At the West House, in room 5, a frieze showing scenes from the town goes round the walls. On the east wall there are scenes of the river, palm trees, ducks, dragonflies and animals. Palm trees are rarely seen in Aegean art, so was this reality or inspired by Egypt? Research carried out in 2014 by Vlachopoulos and Zorzos considered this question and they found that the frescoes showing reeds, ducks and dragonflies have what has been identified as palm leaves pressed into the plaster and painted over, suggesting that palm trees had indeed been raised there before the volcanic eruption that destroyed most of the island.

Lion bones have been uncovered on the Greek mainland and island sites right through to the Iron Age, including near Mycenaean palaces and on the lion hunt dagger mentioned above; a common theme in Egyptian art, but there were no lions in Greece. Yet more examples of Egyptian influences can be seen across the eastern Mediterranean with some rooms in Knossos displaying such scenes and, on Rhodes, there is an offering table carved with papyrus reeds and palms.

This fascinating and beautifully illustrated lecture, gave much food for thought.

July 2024

Dr Enmarch explained that this lecture is based on continuing research, which he is undertaking onthis topic. He began by asking the question “what was a messenger from Sidon doing at the Assyrian

court?” and went on to explore international relations by looking at a number of examples of lesser-known material sources written in cuneiform.

Sidon is a city on the Mediterranean coast, now in Lebanon, and in the Late Bronze Age was a trading city subject to Egyptian influence. Amongst other things surviving texts refer to high status

Sidonians visiting the Assyrian court as vassals of Egypt. Much is known about Egyptian foreign affairs in this region, at the time when Egypt was at its most influential, controlling much of the Syrian/Palestinian territory, whilst the wider Near East also came under the influence of the Babylonians, Assyrians, Mitanni and Hittites. At the famous battle of Qadesh (1274 BC) the Egyptians and the Hittites battled for supremacy over this area, both sides claiming victory - though in reality it was more of a draw. Not that this prevented Ramesses II from bragging about his great victory on

temple walls, stelae and papyri! Texts show that gradually diplomatic negotiations led to peace, and eventually to a diplomatic marriage between the two nations.

The famous ‘Israel’ stela from the reign of Merenptah (1213 to 1203 BC) bears an inscription indicating that the Levant was now considered to be pacified. Egyptian rule there had been under pressure, but several successful battles had stabilised the situation. However, shortly thereafter a series of invasions by the Sea Peoples took place, catastrophically disrupting the Late Bronze Age international political and economic system. Then began a “dark age” throughout the Levant causing the area to decline into a cultural recession. This affected, to differing degrees, all the major players in the area and altered the balance of power across the entire region.

Dr Enmarch looked at cuneiform sources from the late 13th Century BC to consider what happened in the run-up to the reign of Merenptah. A text dated to c. 1230 BC, found at Tel Aphek, show correspondence between the Commissioner of Ugarit (a Hittite vassal) and an Egyptian official in service of Rameses II, discussing some commercial transactions. Another, between Tyre, a vassal of Egypt, and Ugarit, a vassal of the Hittites, refers to a commercial arrangement over the shipping of some wheat, suggesting a peaceful co-existence between them, enabling them to negotiate successfully. Interestingly, a further text has Ugarit approaching Egypt (not their Hittite overlords!)

for aid during a famine; could this be a hint of the start of a shift in power?

Dr Enmarch continued his lecture by looking at the further research he is currently pursuing. He described how evidence suggests that some messengers may have carried more or less ‘official’ communications between the Great Kings of the Late Bronze Age. It was not uncommon for citizens of the Great Kings’ vassal territories to actually serve as their messengers in these circumstances.The suspicion arises as to whether they were only ever strictly intermediaries between the various major states, or maybe sometimes had another agenda. These messengers would stop at waystations, where records of the visits were maintained. Cuneiform sources from an Assyrian

outpost at Tell Huwera in northern Syria, dating to the last couple of decades of the 13th Century BC, give details of the sustenance/hospitality that was offered to foreign delegates en route to Assyria from the courts of Hatti, Amurru and Egypt. A messenger of Amurru appears to be primarily a merchant also charged with a diplomatic mission, but the records relating to a messenger of Sidon,

mounted on a chariot, show he is of higher status. It is unclear whether the Sidonian messenger was a loyal servant of his Egyptian overlord, or alternatively (as has recently been suggested) was

undertaking an illicit intrigue with Assyria, which by this time had reached the apogee of its power.

Unexpected light is cast on this question from a closely contemporary Egyptian-language source dating either to the reign of Merenptah (or, less probably, Seti II). This takes the form of a series of administrative ‘jottings’ copied onto the verso of P. Anastasi III, one of the Late Egyptian Miscellany papyri. These jottings cover a 10-day period and record the comings and goings of messengers to and from Egypt and its vassals/outposts in the Levant. The jottings seem to be made in the Egyptian north-east border garrison at Sile. This document shows messengers with Semitic names (and some with Egyptian names who are sons of people with Semitic names) who are voyaging from Egypt with Egyptian messages and gifts, not just for Egyptian garrison commanders in the Levant, but also for Egyptian vassal rulers, including Baal-termeg Prince of Tyre. The close integration of probably West Semitic language speakers into the Egyptian Levantine communication network makes it perhaps

more likely that the Sidonian charioteer on his way to Assyria may also have been doing the bidding of Egypt. This brought us neatly back to the initial question of “what was a messenger from Sidon doing at the Assyrian court?”

Hopefully Dr Enmarch will return to tell us more when his research is

completed.

August 2024

Neil described how, following a visit to the British Museum to view the exhibition ‘ Ashurbanipal, King of the World ‘, his interest was sparked as he realised he knew little about Egypt’s neighbours and he decided to research this subject. He started by looking at the creation of the city state of Assur, probably around the 26th Century BC and collapsing in 602 BC. He divided its history into 3 periods:

The Early period (2608 to 2025BC). The capital was Assur and was the second to occupy that site, with the first being most likely Sumerian. A terracotta tablet with a kings list is the primary evidence of this period, with king Tudiya (2450 BC) being the earliest and Apiashal (2000 BC) being the latest named. There is also evidence of trade agreements. The second king named on the list is called Adamu, which translates as kings who lived in tents, so a nomadic people who initially lived in tents but became city dwellers.

The Old period (2025 to 1522BC). This centred around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and was a substantial empire including the Assyrians, Sumerians and Babylonians. From around 1450BC onwards, the Mitanni were courted by both Egypt and Assyria. Assur was invaded and conquered by the Mitanni, who set up an effective financial and taxation system.

The Middle period (1394 to around 1050BC). The Mitanni were overthrown. The Hittites sided with Babylon, but the Assyrians captured and destroyed Babylon. North and central Syria were the next victims, then the mountainous areas to the north were captured. These contained significant trade routes. Around 1056BC civil war broke out in Assyria giving the surrounding countries the chance to regain territory.

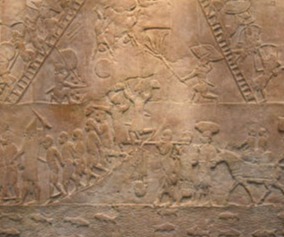

The New Assyrian Empire (starts 911BC and continues to 609BC). The capital was moved to Nineveh, where unfortunately the archaeology is now destroyed after the struggles waged there in recent times. It was largely an agricultural society and the main cities were Assur, Nineveh and Nimrod. The fertility of the soil on the floodplain between the two great rivers enabled the empire to spread widely. Meanwhile in Egypt, between 721 and 707BC, Shabaka, one of the Nubian pharaohs, attacked the Assyrian King Sargon from the south and won; mostly because his enemy was already engaged in fighting his northern foes, so stretched between two fronts. At the Battle of Lachish in 701BC Assyria recovered possession of Nineveh. In the Levant, close to Egypt’s northern border, cities such as Lachish were areas that could cause problems for Egypt. In a similar way to the instillation by some of the Nubian Kings of Amenirdis II and Shepenwepet as God’s Wife of Amun in Thebes, to help the Nubian pharaohs to maintain their power in Egypt, Esarhaddon (681 to 669BC) appointed a Queen in Assyria when the Assyrians were at war with Egypt. Evidence of this was found carved onto pillars and stelae in both countries. Ashurbanipal (669 to 631BC) created the greatest Assyrian empire, based at Nineveh. He was educated, probably literate and often called King of the World, also often seen in carvings killing and fighting with lions. He moved to put down rebellions in areas conquered in Egypt as for south as Thebes, eventually ruling all Egypt for a short time. He even captured and killed members of the Egyptian royal family. Evidence comes from unusual carvings, in the British Museum, of Egyptians fleeing. In 664BC, Tantamani succeeded Taharqa, who had to flee when defeated by Ashurbanipal, and the end of the 25th Dynasty followed. Ashurbanipal died, probably, in 641BC and the Assyrians soon came under attack. A cuneiform tablet records the following, “woe to the Assyrians…….will feel my anger”.

Neil finished by looking at cuneiform writing itself, underlining that it is a script not a language. There are 600 to 1000 characters that make words. It was developed in Mesopotamia and can be called the start of writing. There is evidence from about 3100 BC of administrative documents in the form of pictograms, but from 2020BC characters became formed by wedge shapes instead. They are turned round by 90 degrees and displayed in straight lines; smaller ones can be very hard to read. Information was recorded on clay tablets with a stylus and stamped on, not dragged across like a brush. Portable wooden note books coated with wax could be used and reused as needed. In 1847 four men were given the task of translating the same tablets and it was realised that these marks were texts, which could be deciphered and read. This work has enabled the Amarna letters, a diplomatic dialogue between Egypt and the other major powers of the time, to be read increasing our knowledge of this unsettled period.

September 2024

Dr Griffin, the curator of the Egypt Centre in Swansea, explained how the early 20th Century Grand Tours led to a boom in collecting ancient Egyptian artefacts. Cairo became the hub for trade in all objects as wealthy patrons funded expeditions, often disregarding provenance or ignoring questions about the legality of their methods of obtaining these artefacts.

One of these collectors was Sir Henry Wellcome. In the 1850s he collected thousands of objects from Egypt either from other collections, by buying them or by funding digs himself; some in Egypt but also in the Sudan by buying the right to do so from the French, who controlled digging concessions there at this time. He rarely exhibited his collection, which unfortunately was split up after his death. A large number of objects went to the Wellcome Medical Museum and, not surprisingly, many of the items he had collected showed a connection (sometimes quite loose) to Ancient Egyptian medical equipment and practices.

In 1913, Sir Henry gave a paper on these medical examples, which he had obtained by various means including auctions, private purchases, donations and excavations. Many different auction houses were the source of his purchases. He often went himself in disguise, as sometimes his interest in a particular object led to its price increasing. And, with this in mind, he had a band of agents who were dispatched to various auctions to buy anonymously on his behalf.

He funded a number of excavations in order to benefit from his patronage, by being presented with some of the finds as a reward for his financial support. In 1910 and 1913 helped fund Petrie’s excavations in the Sudan. In respect of private acquisitions, in 1929 he authorised purchases from Gayer Anderson and bought 4000 amulets from Winnifred Blackman. In the 1930s Peter Johnson Saint became his paid collector in Luxor, sending his purchases back to the Wellcome Medical Museum.

He donated objects to the museum himself, including casts of artefacts with a medical theme, where the originals were held in Cairo Museum. These often had the base and sides covered with medical texts and spells. But although he had great buying power due to his enormous wealth, he favoured quantity over quality buying many objects from dubious characters like Mr R de Rustafjaell, who was allegedly born on the 10th of December 1859 in Russia; however there are many inconsistencies in his personal history as he uses different names, birthplaces and marriage partners. He converted to Islam and took an Arabic name before moving to New York becoming Prince d’Orbeliani. He lived in Luxor for some time as a dealer selling mainly fakes, commonly fragments of Theban tombs. He died in 1949 and his collection was sold off, but who knows if any items were genuine? In 1906 he had sold £1000 worth of objects, including items from an auction lot no.139, to the British Museum for £27, with one artefact being an early, possibly 6th Dynasty, figure of a man walking. Catalogue pictures of the lot are of good quality.

Dr Griffin showed us many fascinating examples of how archived catalogues from the various auctions had helped in identifying the objects dispersed after Sir Henry’s death, including many in the Swansea collection. Clear photos of the lots and hand written notes by Sir Henry’s agents in the margins of the auction catalogues were invaluable in making the identifications. Notes included which lots to bid for and sometimes the limit on the price to be paid. The National Museum of Scotland, through their agent Mr Laurence, bought lot no.149 for £13 and lot no.141 for £15 at one auction. However, according to the records some of the funerary boats from these lots were later destroyed as fakes. This shows that buying agents often had little knowledge of what was authentic and what was counterfeit. Buyers valued wall paintings chiselled from the tombs at Thebes. De Rustafjaell had removed and sold, usually illegally, a number of these panels and catalogues show 16 lots sold to museums, 4 to Sir Henry and 2 to the British Museum. Bidders identified from these catalogues included Sir Henry Wellcome himself occasionally as well as his agents. In one instance CJS Thompson, the first curator of his museum, bought 244 items for £644.11 (40% of all lots at one particular auction). He was told to make sure no one found out he was bidding for the Wellcome Museum to prevent price hikes. He had an agent’s catalogue in the Wellcome Collection and many of the textile fragments there were identified using lot numbers from this. Most of these objects have no provenance but their modern acquisition history can be worked out using these catalogue descriptions, although a few do have a geographical link; EC303 is from Armant , WI435 from Aswan and EC703 from Medamud.

Sir Henry’s collections continued to grow but there were fewer sales as more and more fakes were identified. At the 1911 sale at Sotheby’s HC Bourne was entrusted to buy 641 objects, mostly amulets, statues and deities. The collection of Lady Valerie Meux (1847-1910) was sold. Sir Henry’s agents bought 9 lots comprising of 70 items for £54.15, including a statue of Amenemopet, identified by Boscowan as Chief of Physicians at Thebes (and now in the Petrie Museum). H M Kennard bought a statue of Imhotep, the patron god of medicine as well as 6 other figures for £37.15. At the sale of the Reverend William MacGregor’s collection in 1922, Wellcome bought, either himself or through one of his 5 agents present, 22.1% of the items on sale.

He began to implement a new system of recording the items in his collections by using catalogue cards with a label showing a registration number and a description of the place acquired plus purchase information, and also its measurements. This gave some provenance (if only modern) to many items such as lot 1798, with tiles, amulets, jewellery and a bronze whistle from the Step Pyramid at Saqqara. There is no doubt that Sir Henry’s collection was on a huge scale and reflected his personal interest in and knowledge of ancient Egyptian medicine, especially of Imhotep, which he could indulge in due to his great wealth. This sparked public interest, especially in medical ideas and instruments. Sadly his heirs did not follow his passion and his collection was broken up on his death. However, he certainly contributed to the greater knowledge and understanding of ancient medicine in Egypt by the creation of and support for his collection.

October 2024

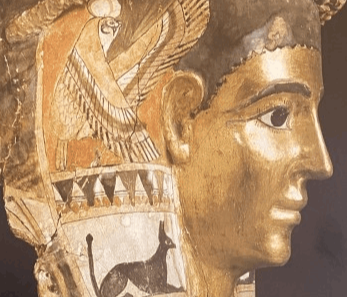

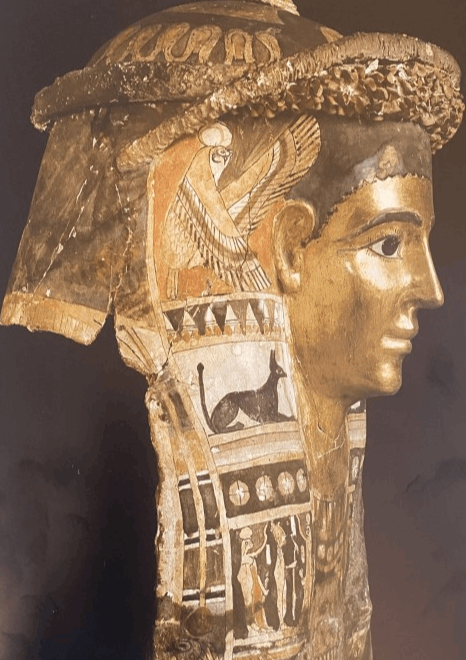

Judith is a firm favourite with Wirral Ancient Egypt Society and has delivered a series of lectures over the last few years relating to different aspects of funerary practices in her specialist time period; the Greco-Roman. On this occasion she looked at coffins and sarcophagi, plus the associated funerary masks found with these burials. Her highly informative and interesting lecture was beautifully illustrated with examples of the many different forms and gave us a comprehensive view of the practices at this time. This had initially been billed as the final lecture in this series, but we are delighted that Judith has agreed to return again in 2025 to talk to us about the use of cinerary urns.

November 2024

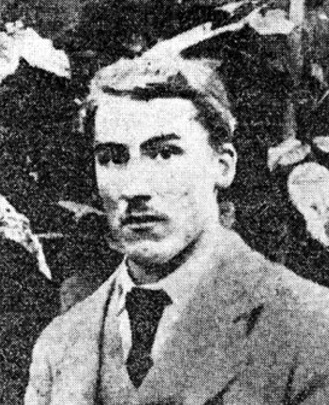

Claire Ollett has been fascinated by Howard Carter for years. Mainly known for the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, she started to research what else he did prior to this, after recognising many of the comments about him were based on jealousy and prejudice.

She researched his early life. He was born in London on 9th May 1874 to Samuel Carter and Martha Carter, who both originated from Norfolk. His father was a talented artist who painted local animals and leading local figures. Howard was the youngest in a large family of 11 siblings and was a frail child who had a limited education and was moved from London to relatives in Swaffham in Norfolk. Four of his siblings made their living from painting.

In Norfolk the owner of Didlington Hall, William Amherst, was a great influence on Howard Carter’s development and helped him find his first position with Percy Edward Newberry, an archaeologist involved in the study of tombs in situ, by recording them in drawings and paintings. Previously Howard had become very interested after visiting a small collection of Egyptian artifacts and had already come to the realisation, aged 16, that he would have to make his own living. We know that Howard was assisted by the Amhersts because Lady Amherst wrote a letter to Percy Newberry thanking him for finding him a position with the expedition and she personally commissioned paintings of sites in Egypt from Howard.

In 1891, before he was due to travel, Howard spent 3 months in the British Museum practicing drawing objects there and learning what he could of Egyptian history. The journey first took him to Alexandria, then overland to Cairo to meet Flinders Petrie. From there Howard travelled to Beni Hassan where he worked with 3 other artists and lived in a tomb, about 200ft above the valley floor, on a very modest salary. His job was to trace and record the images on the walls of the tomb of Khnumhotep. Newberry became convinced that this method of working was inferior to free hand drawing which was more accurate.

At El-Bersha he was given the job of drawing the scene showing a huge statue being dragged on a sledge by hundreds of workers in the tomb of Djehutyhotep. On the 21st December 1891, he met 3 Bedouins who described the site of a tomb nearby, hopefully, he thought that of Akhenaten, but instead he found the Hatnub quarry – the one mentioned in the scene he had just been copying from the tomb. A disagreement arose between the group of four artists, as on the 28th December, Blackden and Frazier claimed they had found the quarry and published drawings declaring it as their discovery. Carter and Newberry separated from them after this fall out.

In 1891 Flinders Petrie had offered to train up a young artist in how to excavate. He now gave this opportunity to Howard instead of Blackden. Amherst was in agreement as he hoped to gain some of the artifacts found as a reward for his sponsorship. Although Petrie agreed to the placement, he initially felt that Howard was only interested in painting and drawing. However he soon changed his mind and was very impressed, after giving him an area to excavate on his own, by his care and precision when digging. A piece from this Petrie dig at Amarna from the Amherst Collection is now in the Atkinson Museum, Southport. The dig ended in 1892, by which time Howard had learnt a great deal, though still only 17.

In 1893 Carter worked at Deir el-Bahri under Edouard Naville, where he mastered photography, learnt Arabic, to be able to converse with the local workers, and got involved in the reconstruction of the temple there. He met a lot of important people in Egyptology at this time.

In 1894 one of his brothers visited to work with him and painted a copy of the vulture on the wall opposite the area Howard was reproducing, which demonstrated that they painted in a very similar style. Howard liked to visit the original at different times of the day to ensure he got the best representation of what he was working on. He believed in ”honest work, freehand, a good pencil and suitable paper”.

He produced many examples of drawings of birds and animals. To ensure he drew in the Egyptian manner, he worked closely with Edouard Naville, who considered him to be multi-talented saying it was “remarkable how well that difficult work of rebuilding is being done by Mr Carter, who has a quick eye and a remarkable grasp of Arabic”.

Howard was made Chief Inspector of Upper Egypt, putting him in charge of every excavation and site there. He was described by Maspero as “obstinate, but active and capable - positive traits that usually worked in his favour”. He implemented many changes, increasing security as robberies were common, including a 24 hour security force and putting wooden doors on tomb entrances with iron grills in front of them. He arrested a family of notorious locals for tomb robbing, but they were tried and found innocent. Later, however, he saw a stolen funerary board being sold by one of the brothers, so was proved right after all. He also worked at Kom Ombo, Edfu, Philae and Abu Simbel and on other excavation sites.

But he really wanted to work in the Valley of the Kings and to achieve this he needed to find a wealthy sponsor. Theodore Davis had the concession and employed him in 1903 when he found the tomb (KV43) of Thutmose IV. Howard also worked in KV20 (tomb of Hatshepsut) finding the sarcophagi of her and her father as well as some canopic jars.

In 1904 he was transferred with the Antiquities Service to Lower Egypt. At Saqqara one day some French tourists arrived and in a rude manner demanded to see the Serapeum without buying tickets, then became aggressive and manhandled a guard. They marched up to the excavation house and demanded to see the supervisor. Howard demanded they leave. The French men began hitting the guards so Howard told them to defend themselves and, after a fight broke out, the police and Maspero were informed. All the French men worked for the Cairo Gas Company and complained to their employer. There was a diplomatic incident but Howard refused to apologise and lost his post. Subsequently he was moved to Tanta in the Delta, which he believed was a downgrade and on the 7th November 1905 he resigned.

A short time later Lord Carnarvon visited Egypt to recuperate after an accident. Howard returned to drawing and painting and produced one-off pieces of work for buyers like Davis and Arthur Weigall, Chief Inspector of Upper Egypt from 1907. Lord Carnarvon bought the rights to dig at sites in the Luxor area and asked Howard Carter to provide the professional help he needed with his excavations. In 1909, Maspero wrote that “it is good to see Howard Carter back into excavating”. In his first season he found numerous objects and built his house on the West Bank. Still his dream was to work in the Valley of the Kings.

In 1914 Theodore Davis decided to give up his concession in the Valley of the Kings. He and Maspero declared the Valley was exhausted and that further excavation was a waste of time. As for what happened next … we hope Claire will return in the future to details the exciting events that then unfolded.

December 2024

Presidential lecture after the AGM

December 9th 2024

Dr Ashley Cooke

Current Research in Egyptology at the World Museum, Liverpool.

Dr. Cooke began by thanking the Society for the gift of a slate plaque depicting the god Ptah. He then started his lecture, bringing us up to date on what is happening currently at the World Museum.

Last year, he explained, the World Museum hosted a project on Animal Mummies and selected 22 for study from their extensive collection, choosing those in distinctive wrappings. He reminded us of the events in 1890 when a shipload of such mummies had been ground up for fertiliser after arrival at Liverpool docks. Another study looked at Roman Period mummies from the Western Desert, especially those in cartonnage coverings.

Another ongoing project is looking at the whereabouts of some of the material from the Garstang collection, both in the UK and worldwide. Some artifacts in the stores also are being put online. The Garstang Museum has a large collection of photographs which, if digitalised, will make access from across the world much easier. This would be similar to the one organised to source objects excavated by Flinders Petrie.

In 1884, the Egypt Exploration Fund, with Petrie, began to keep very detailed excavation records. He trained Garstang accordingly, but did not see eye to eye with him and Garstang set up his own method of archiving in Liverpool using very different methods. Sadly many of the records kept in Liverpool were lost or destroyed during bombing in World War II.

Between 1884 and 1915, Garstang created the biggest and most significant collection of artifacts (2720) outside the British Museum. He had arranged with the Egyptian authorities that he would have the pick of what was found in his excavations, after the best objects were chosen to stay in Egypt and exhibited there. Unfortunately, it often happened that separate parts of broken objects were displayed in different places. Parts of a broken piece could end up with half in Cairo and half in Liverpool. Though Garstang had a smaller group of sponsors than Petrie, mostly based in the North West, they still all expected to receive from him items for their own private collections. He called them his Committee and many kept their own archives and proof of purchase showing when and where the artifacts came from. In his 1904 advert in The Times he offered excavated items for sale from his digs to members of the public, usually academics, consequently many objects were scattered around the world and some ended up damaged by fire, earthquakes etc.

His method of using the Committee to sell artifacts has led to losing track of some of these objects and many are spread across the globe and described as lost. In the very early 1900s a new extension was built onto the museum creating huge new galleries and the collection was moved from the basement to these new spaces. At this period in time Garstang excavated at Esna and his excavation notes were published in detail. He received some animal mummies, shabtis and a wrapped crocodile egg from the excavation there.

In addition, in Nubia, encouraged by the French Antiquities Service, he excavated above the Aswan Low Dam, which was being constructed, where many valuable sites were being lost to the water. Here Harold Jones was employed to keep a record of excavation notes, drawings, photographs and huge amounts of ceramics were found at some of the sites. Garstang’s initial report showed his excitement and finds were carefully labelled. He thought he had found his next big site in Nubia but, sadly, soon discovered that it had been looted both in antiquity and in the present day. The Cemetery only produced beads, some shabtis and pottery buried as grave goods.

In1906 artifacts were split into 10 divisions/lots between members of the Committee, who could do what they wished with them. Some were sold, some kept in private collections or split up and given away to museums, thus spreading related objects around the country, even the world. Some of the original catalogues were still kept in the archives though.

Through this funded project Dr. Cooke is now attempting to bring objects from these excavations together again. During the 1920s many of these private collections were sold off by their owners. Some were bought by archaeological institutions, such as the Metropolitan Museum New York, Bolton Museum, and the Liverpool Museum. The Danson collection, for example, was obtained by the Liverpool Museum in 1976 containing many objects, photographs and letters giving details from excavations. Some of the items at Liverpool were identified as being from the Danson collection, with some discovered at Abydos and Esna along with details in the archives of when and where they were bought and by whom. One item was identified from a photograph as being from the 1907 Danson collection, now in the Garstang Museum. Another item was spotted on a photograph of the buyer’s house in the Lake District; this Committee member gave it back to the museum. The same photograph shows what is still missing from the same division. Are these objects in another collection in the UK or taken and sold overseas?

Using technology to digitally record collections means that items now scattered across the world can be traced and possibly be reunited with those found in the same excavation, or even two or more segments of the same piece, now in different collections, can be reunited to give a clearer picture of Egyptian history – even if this rejoining is achieved by means of a digital image. This is indeed very valuable work.